http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/realestate/2008587017_realneighborhood04.html

By Tim Harville

Special to The Seattle Times

Originally published January 4, 2009 at 12:00 AM

Thrill-seekers shrieked on “The Dipper,” the park’s famous roller coaster, while young couples stole first kisses in the Canals of Venice. Dance marathons brought thousands to The Ballroom, and a midget auto-racing track filled the air with a steady roar for the park’s neighbors.

Broadview and Bitter Lake were annexed by the city in 1954, and Playland shut down in 1961, upstaged by the impending Seattle World’s Fair. Today’s Broadview is a much quieter place — an almost completely residential neighborhood, tucked so snugly into Seattle’s northwest corner that many locals have never heard of it.

“Nobody knows us,” says Dale Johnson, president of the Broadview Community Council. “You say Broadview and people think Broadmoor” (the gated community just west of Madison Park).

Despite its low-key demeanor, the neighborhood is by no means small. Home to more than 13,000 residents, Broadview stretches north from Carkeek Park up to the city limits at Northwest 145th Street, and east from Puget Sound to Greenwood Avenue North.

Apart from a handful of restaurants and retail spots along Greenwood, Broadview has very few commercial offerings. While construction of condominiums and apartments is increasing (and concentrated along Greenwood), most homes are single-family.

According to Joanie Brennan, a longtime Windermere Real Estate agent who specializes in North Seattle homes, many buyers are drawn to the open floor plans of Broadview’s midcentury homes.

Brennan says the market in the neighborhood is somewhat split along Third Avenue Northwest.

To the west, near Carkeek Park and along the waterfront, are the more-expensive homes, many with large lots and Puget Sound views.

To the east, between Third and Greenwood, buyers can find smaller, more affordable options. Overall, the median price of a single-family house that sold in Broadview was $422,000 during the first 10 months of 2008, according to figures compiled by Windermere Real Estate. Of the 76 houses sold in Broadview, the prices ranged from $280,000 to $1.965 million. The typical house was 1,935 square feet with three bedrooms and 2.5 baths.

Many residents say they appreciate the quiet Broadview offers while still being close to downtown.

“Broadview is in the city of Seattle, but feels a bit suburban because of the large lots,” Brennan says.

Commuters can easily get downtown along Aurora Avenue, by bus or car, without taking any freeways.

Will Murray, who has lived in the north end of Broadview for about 10 years, enjoys an easy commute without driving.

“I like being able to walk to the bus stop and be downtown in 15 minutes,” he says. “Also, I can bike downtown in 45 minutes.”

If nearby Playland’s thrills and entertainment made up Broadview’s identity in its adolescence, nature and conservation are integral themes in today’s more grown-up community.

Carkeek Park, the neighborhood’s largest park, offers more than 6 miles of trails. A pedestrian bridge over the railroad tracks offers views of Puget Sound and the Olympic Mountains before descending onto a secluded, sandy beach.

Another escape into nature, and one Broadview’s best-kept secrets, is Llandover Woods, a 9-acre “open space” at 145th and Third Northwest and acquired by the city of Seattle in 1995.

“Llandover Woods is a major success story in northwest Seattle, saved from a housing development by neighbors and being restored to native habitat,” Murray says, adding that “the woods are a great place to hike, bird watch, and forage for mushrooms.”

Another often-overlooked gem is Dunn Gardens. Commissioned by Arthur Dunn in 1915 and designed by the legendary Olmsted brothers, the original landscaping plan of the gardens has been preserved for more than 90 years.

“It’s lovely in winter, spring, summer, and fall. Any time you go, it’s beautiful,” says Gloria Butts, coordinator of the Broadview Historical Society and former president of the Broadview Community Council. “In February, cyclamens and snowdrops are in bloom, drifts upon drifts of them.”

Dunn Gardens is open to the public for guided tours only, Thursdays-Saturdays, by advance reservation.

Broadview’s “green” leanings are even reflected in the infrastructure. The neighborhood is home to Seattle’s pilot Street Edge Alternatives project, or SEA Streets. These slim, wavy streets, located just west of Greenwood between 110th and 120th, are designed to improve drainage by using natural landscaping and swales to slow and filter stormwater runoff.

Much of Broadview’s population is older, and turnover in the area is relatively low.

“I was a newcomer 10 years after I moved here, so many people had lived here so long,” says Butts, who has lived in Broadview for 45 years.

Perhaps because residents tend to stick around, a strong sense of community is another cornerstone of Broadview’s personality.

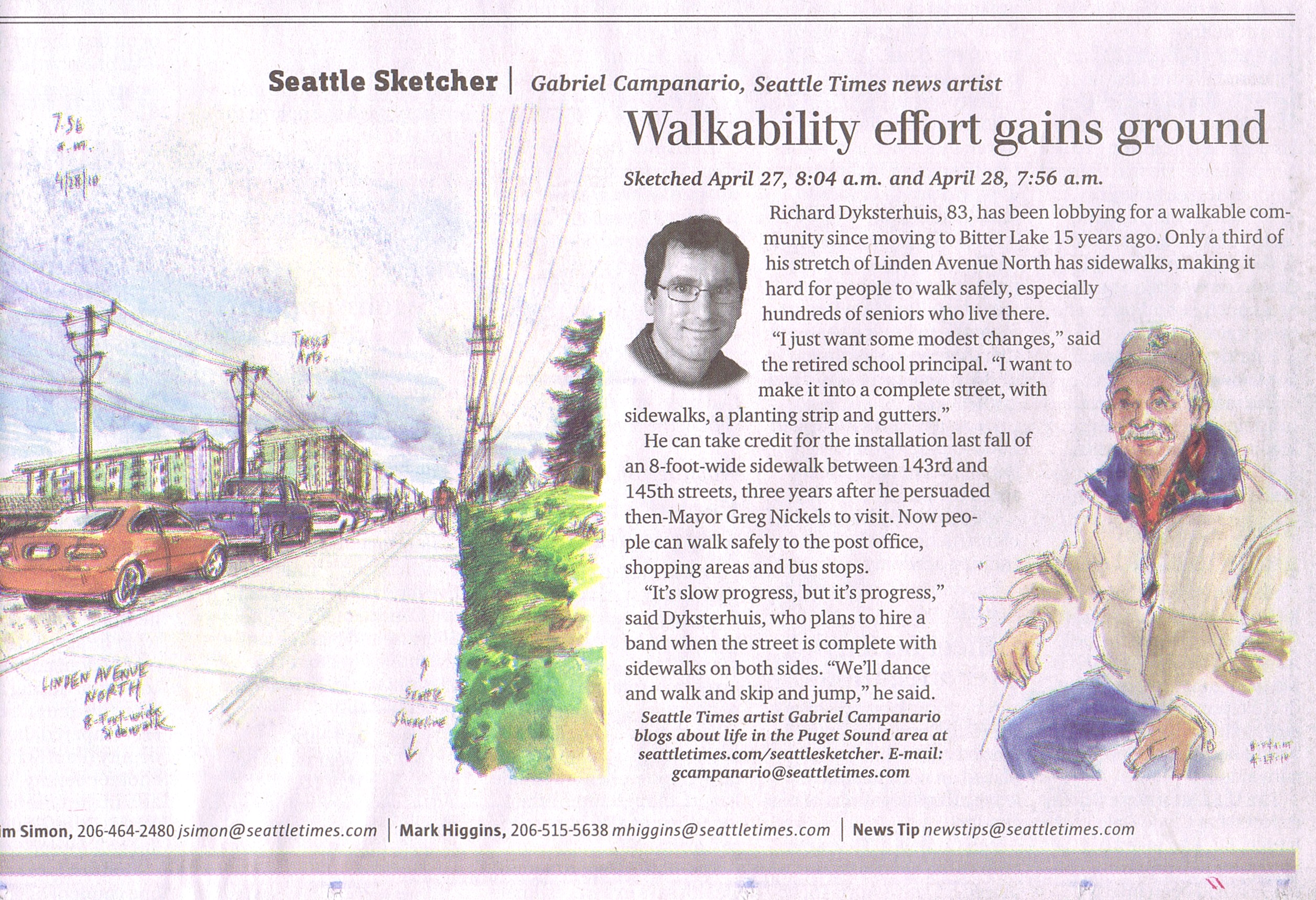

At a recent meeting of the Broadview Community Council, which convenes at the library, pedestrian safety was the topic of the evening. Members of the community were joined by representatives from Feet First and Seattle Great City Initiative to talk about the one thing Broadview seems to lack: sidewalks.

Many residents of old Broadview thought that being annexed by Seattle would bring in such perks of the “big city” label as sidewalks. But today — 55 years after becoming part of Seattle — the neighborhood has yet to see a complete, fully sidewalked street.

Attendees at the community meeting were mostly longtime residents of the neighborhood, and a few were actually around when Broadview became part of Seattle.

They’re used to working together to get City Hall’s attention, maintaining dialogue with their city and state representatives, and using civic vocabulary (for example, LID for “Local Improvement District,” a method of funding public projects) like seasoned professionals.

“In the past several years there has been a resurgence of activism, with several volunteer groups forming and doing community service projects such as Adopt-A-Street, Llandover Woods, Carkeek Park Trails, and Teen Groups at Bitter Lake” says Murray.

To Butts, it’s this community spirit that makes the neighborhood a great place to live.

“The people who live here really do care,” she says. “They take care of their space — you don’t see any litter — and there are enough people willing to work for solutions, enough volunteers in the Community Club and the Community Council doing things to make the area better.”

Copyright © 2009 The Seattle Times Company

BROADVIEW

Population: About 13,000

Distance to downtown Seattle: About 10 miles

Schools: Broadview is served by Seattle Public Schools.

Recreation: The 216-acre Carkeek Park contains orchards, creeks, picnic and play areas, hiking trails along steep wooded hillsides and views of Puget Sound and the Olympic Mountains.

— Seattle Times news researcher David Turim