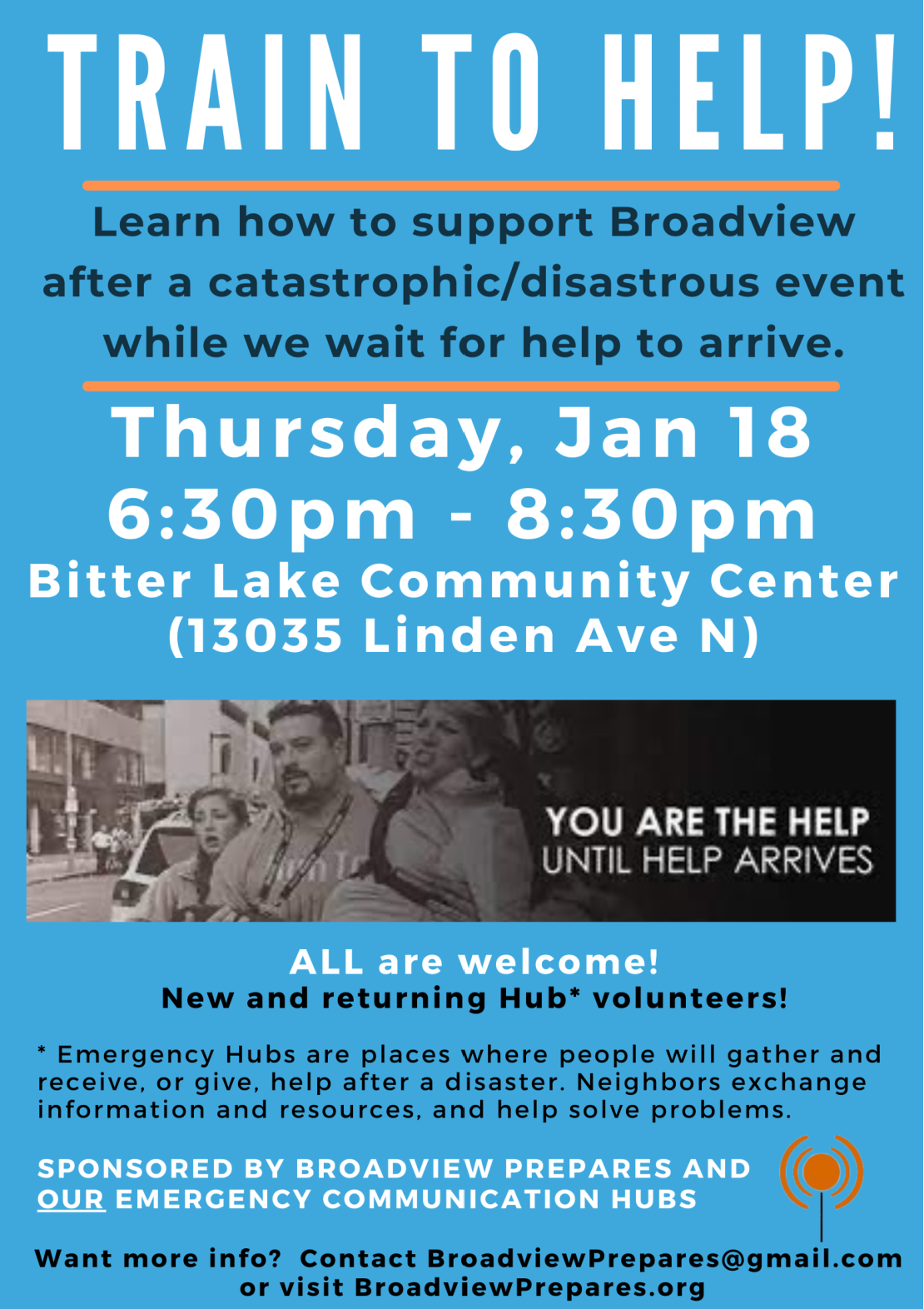

Be “Rumble Ready”– Practice Earthquake Response with Your Neighbors

If Seattle were to experience an earthquake or another large, disruptive event, are neighbors ready to support one another until help can arrive? The Seattle Emergency Communications Hubs are here to help and they are holding their major yearly practice on June 1 and June 9. The sessions are all the same and take place in multiple locations across the city on two separate dates.

Each event is a practice scenario where you will:

- Gather and share information (some gained by amateur radio),

- Set up resource sharing among neighbors,

- Deploy volunteers efficiently, and

- Share valuable information.

See Broadview information below.